For the love of all things difficult

As a material, glass is fundamentally untameable. It may be straightforward enough to melt and ease into a mould but there is ultimately no control over the final outcome. This is precisely what fascinates artist Renata Jakowleff, who continues to pursue perfection through glass, despite knowing she will never achieve it.

“No other material is as challenging or as difficult to work with. With glass, there is no way you will ever nail it 100 per cent,” she says.

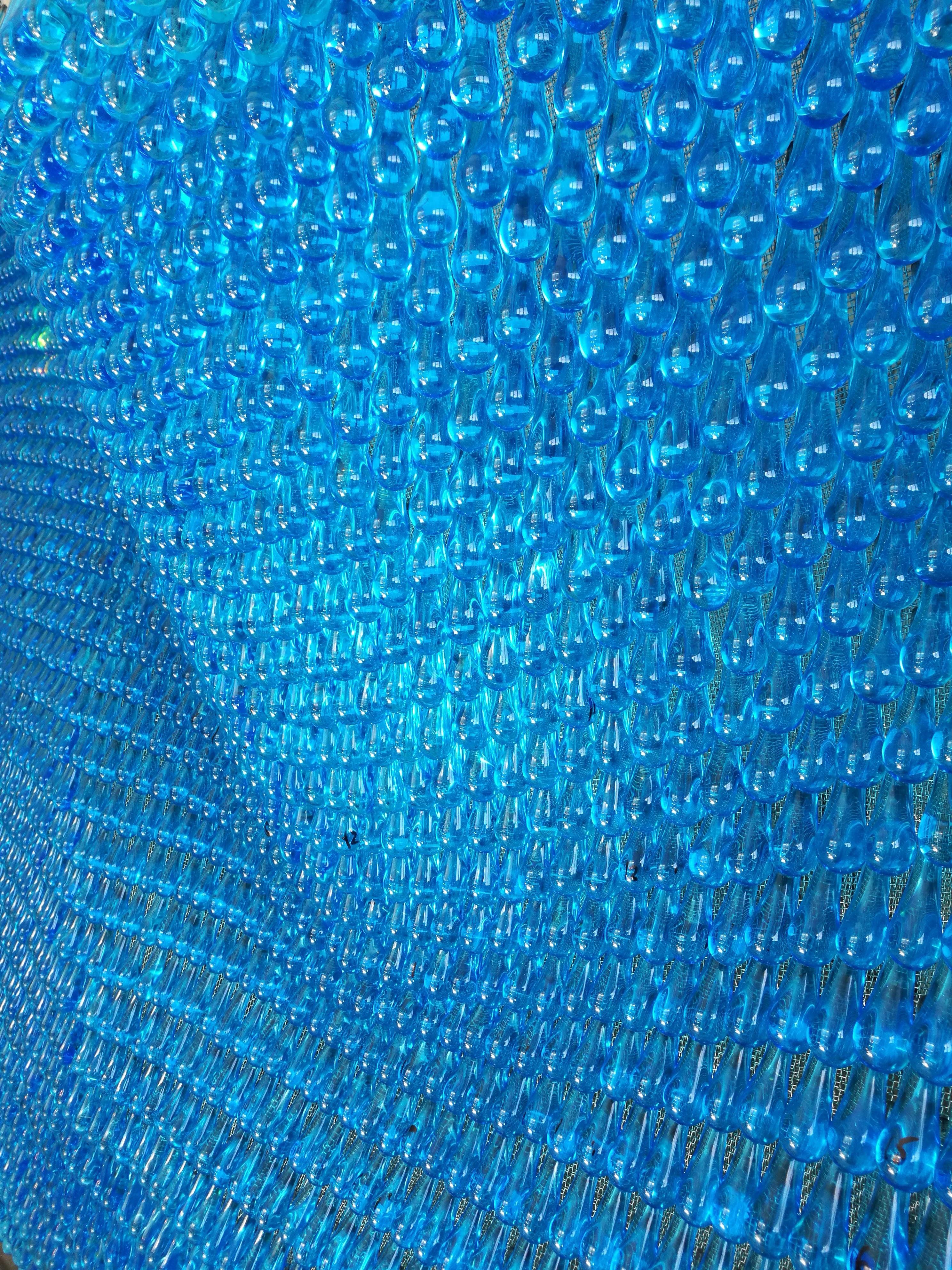

“What first attracted me to glass was the craftsmanship, the practical aspects of glass working. Glass is such a reactive and responsive material, a living thing, really. That might sound like a bit of a cliche and people don’t often stop to think what it actually means but what I’m trying to describe is this sense that, when I work, I am in dialogue with glass.”

The story continues after the pictures.

In Finland, glass artist are few in number and their 1950s heyday is well and truly over. In fact, Jakowleff is one of only a few practitioners in Finland who is actually able to make a living from glass art.

“There are so few of us in Finland that all the innovations and advances that have taken place in recent years have been driven by the individuals themselves. As it happens, there are now just two or three larger glass workshops in all of Finland.”

After she graduated from art school, Jakowleff would set her alarm at 5 am, gather her things and head off to work in rented studios in Nauvo, Riihimäki and Nuutajärvi.

“That was pretty tough. I actually lived in Nuutajärvi while I used the workshop there. With studio rents being so expensive, everything you did had to be carefully planned in advance. There was absolutely no room for spontaneity or experimentation,” she says of her early career.

Things took a more positive turn when Jakowleff was able to secure a studio on Suomenlinna island outside of the Finnish capital, where she could test her ideas, experiment and work more intensively.

“At Suomenlinna I first started using smaller individual pieces to create larger works. When it comes to artistic practice, your outcomes, what you’re able to achieve will often be dictated by the practical circumstances you’re faced with.”

In terms of scale, glass working is always defined and limited by the artist’s own physical presence – you simply cannot work on a piece that is large than your own body.

“You have to be able to lift up the molten glass using a blowpipe so that limits the maximum volume of glass you can work with. It doesn’t matter if you have five big guys lending you hand, you’re still limited to this sort of size,” Jakowleff says, using her hands to draw a half-metre wide shape in the air.

Jyväskylä’s Kangas residential neighbourhood is currently home to a retaining wall that has been textured using the muotobetoni (form concrete) method. The dark grey surface looks more like a magnificent draped curtain than anything solid. Visitors can spot it on the way towards the communal garden. The new muotobetoni concrete technique is Jakowleff’s other bread and butter pursuit and one that happens on a rather different scale from her glass work.

“It involves a completely different level of responsibility. I could never let go of a piece of work that I wasn’t totally happy with, as it is. But when you make something out of concrete, you know it’ll still be standing a hundred years from now. And when we manufacture these elements, it’s deadly serious stuff. The sheer scope of each piece huge and we leave nothing to chance.”

With hindsight, it makes perfect sense that it was Jakowleff that ended up creating the muotobetoni technique. She says it is a logical part of a creative continuum, after all, concrete, just like glass, is a liquid material that can be moulded and manipulated at will. Recently, Jakowleff was asked to go and give a talk on her the muotobetoni technique in Hungary. She turned down the invitation.

“I’m at a stage with this technique where there’s absolutely no point in trying to disseminate my know how. My job right now is to continue to hone the techniques and dedicate as much time to that as I possibly can. Coming up next is a complete muotobetoni collection that will feature some prints by Finnish design duo Elina and Klaus Aalto.”

For Jakowleff, art has been a presence in her life ever since her childhood. Right now, she is sanguine about the fact that mega star crooner Sir Elton John purchased one of her glass artworks for inclusion in his private collection in 2014. As far as Jakowleff in concerned, the main thing is they’re selling.

“I’m not about to start resting on my laurels, quite the contrary. I’ve always had an incredibly high work ethic. I work hard and this grant funding gives me a great sense of responsibility. This is my job and I need to do it well. I want to make sure I earn my salary.”

2005 Renata graduates with an MA from Helsinki’s University of Art and Design

2006 Corburger Glaspreis competition, Germany

2015 Seminar event on concrete run by Ornamo and Rudus

2017 First precast muotobetoni concrete installation, a retaining wall, is erected in Kangas, Jyväskylä, Finland

2017 “Blue” unveiled at the entrance to Aalto University’s Dipoli building

2018 Renata announced as the recipient of a three-year Arts Promotion Centre Finland grant