Critical curiosity for schools

The Designakatemia is a collaboration between Ornamo and the Architecture & Design Museum, which has been taking designers to lead design courses in various schools in Helsinki for 15 years. This time, the schools were visited by Paula Karvonen, Hannakaisa Pekkala and Inka Saini.

Designakatemia’s design courses develop students’ problem-solving skills, interaction and emotional skills and strengthen the schools’ sustainable values. Depending on their area of specialization the designers create a design thinking course for the students. The course is integrated into the school schedule according to the teachers’ wishes, and the students have an opportunity to visit the Architecture & Design Museum. The courses are co-funded by Helsinki City.

Perspectives, viewpoints and embodiment

Service designer Inka Saini tested her new design concept at the Designakatemia, which offers the children ways to develop their future skills. Inka is a professional in spatial and service design with a background in elite sports as a competitive gymnast.

This unique combination of expertise was evident in the design course at the primary school of Käpylä Comprehensive School. The pupils explore the school’s facilities from many different perspectives, and especially with the help of embodied learning.

The children drew the outline of their own bodies in 1:1 proportion. With these self-portraits they explored both their inner feelings and their relationship with the surrounding space. While lying on the floor, the school environment was seen from a frog’s perspective, and the bird’s-eye view was experimented by looking at the immediate environment on a map. Through movement, presence, and concentration exercises, children learn to recognize the connections between space, body, and emotions.

“As a service designer, I am interested in the different worldviews of adults and children – without children’s voices, we easily make assumptions about their needs,” Inka says.

She points out how, for example, the museum experience of the future, shaped with the help of artificial intelligence, may reflect more the ways of thinking by adults. When the children were asked what they would like to see at the Design Museum, one answer was: my own family.

During the project, the children deepened their self-knowledge and identified how spaces can reflect emotions – and vice versa. The bodily exercises also created moments of interaction: for example, the teacher could just pet a child who needed attention.

“At the Designakatemia, you learn to appreciate the work of a teacher, whose everyday life is often punctuated by a rush – just like working life in general. I was able to get into the everyday life of the school, but at the same time I got a lot of tools for my own work and how connection can create space for genuine encounters,” Inka sums up.

The course culminated in the opening of the City of Emotions exhibition at the Design Museum, which was built from recycled materials.

Tape, Paper, Scissors

At Vuosaari Upper Secondary School, designer Hannakaisa Pekkala was surprised when the teachers hoped that the assignment of the design course would focus on handicraft. To counterbalance digital life, there is clearly a need for more traditional skills: the interaction between hands and thinking.

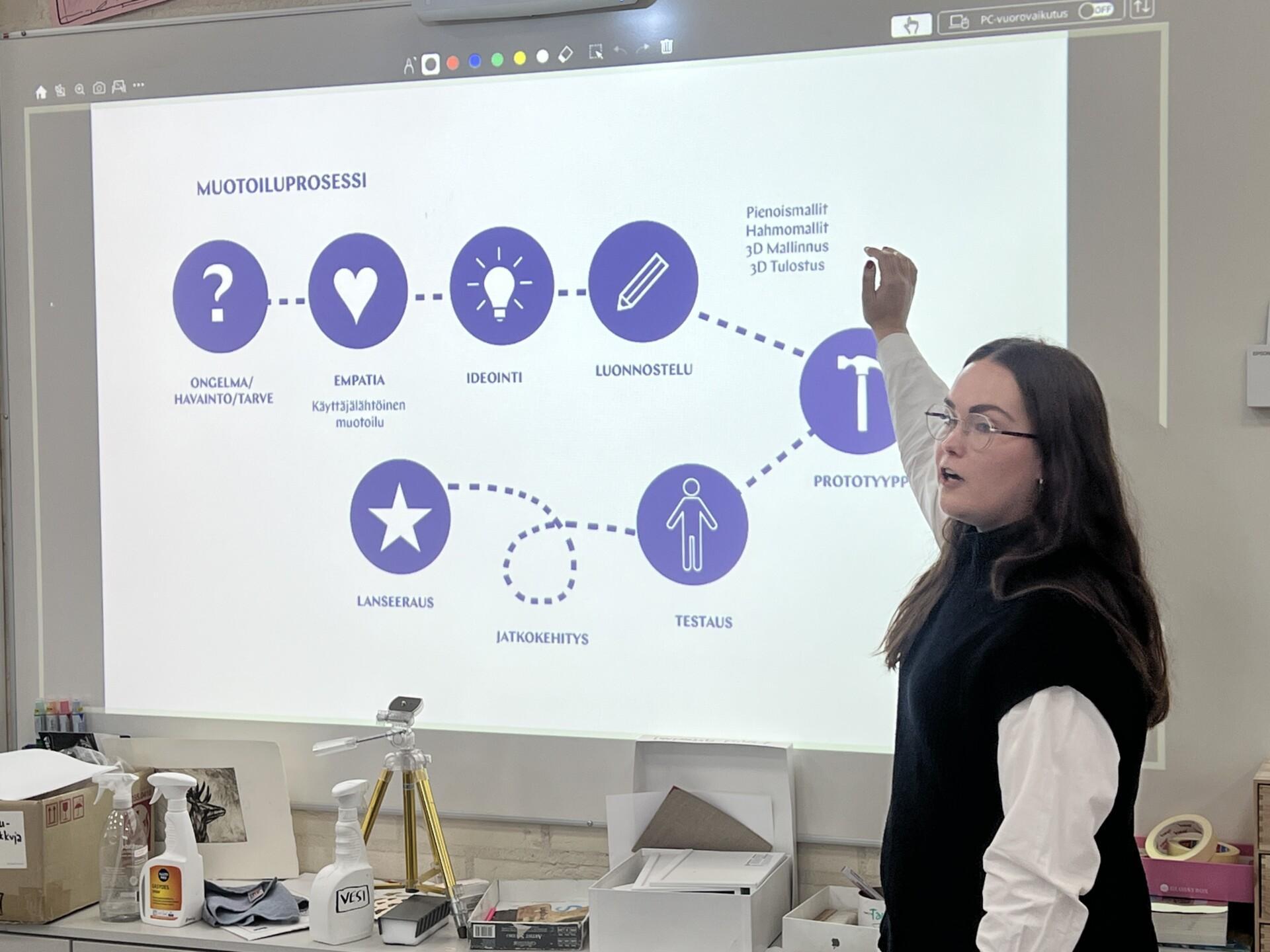

However, the Designakatemia always starts with thinking, not crafting. In Hannakaisa’s product design course, upper secondary school students first got to know the profession and concepts of a designer. After that, the existing artefacts were considered by analysing familiar artefacts.

“It came as a surprise to the students that Eero Aarnio designed the famous ‘ball chair’ already in the 1960s. When we then discussed that era of space travel, aha moments arose about the shape of the chair. This also opened their eyes to why a design task always starts with observation and only then progresses towards brainstorming,” Hannakaisa says.

Hannakaisa’s design assignment sought solutions for the school environment.

“It was challenging for the upper secondary school students to let go of the idea that everything has already been planned, or that they can’t plan if they don’t know how to draw. This was tackled well by building scale models, because the students realized that you could create a really good character model with just tape. It provided experiences of success, especially for those students who did not feel that they were good at the traditional methods of visual arts. In design learning, everyone gets to shine in their own way,’ Hannakaisa says.

Caretakers of the Future

In designer Paula Karvonen’s course, the seventh- and ninth-graders of Puistopolku School were introduced to critical thinking, which is important in design work. At the beginning of the course, the students compiled collage-like interpretations of their use of time and their environment. They highlighted their interests and societal perspectives, both as individuals and as a group.

“The understanding of design thinking opened up through exchanging thoughts on everyday school situations, emotional connections and experiences of chaos. I aim for a multidisciplinary and participatory approach that combines environmental and natural sciences, aesthetics and philosophy, situational thinking, the ties of time and place, and ethnography,” Paula says.

With Paula’s guidance the students studied biophilia, i.e. the innate or learned connection of humans to nature, and how the experience of nature is utilised in design.

“In the design task, a lamp model was created that had to take into account the material cycle, circadian rhythm, seasonality, connection, natural light and connection to nature – all factors that support people’s well-being, sense of community, and the theory and value base of my design thinking,” Paula continues.

During their visit to the design agency Pentagon Design, the students got to play an expert role with service designer Laura Hieto: to brainstorm a space of their dreams for a library under construction in Helsinki.

“Cooperation with an agency showed how companies can carry social responsibility together with schools. When the young people received direct feedback, they noticed that their own ideas were meaningful – especially in the design of public spaces,” Paula says.

Increasing inclusivity in schools is one of the key goals of the Designakatemia. However, equality is not necessarily achieved by following the DEI rules created by adults, but by genuinely involving students and teachers in the planning of the environment.

“When we ask young people, we notice that not all of our solutions necessarily create spatial security. For example, young people of a certain age and a unisex toilet. At the Designakatemia, I learned that schools have a huge amount of invaluable information that should be listened to, respected and used,’ Paula says.